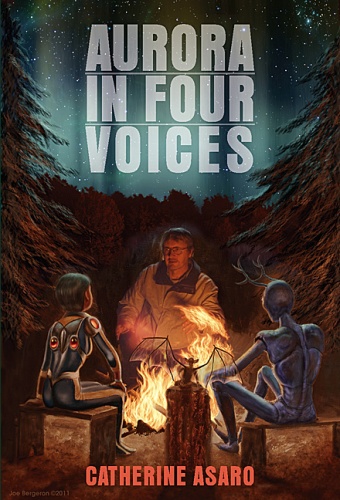

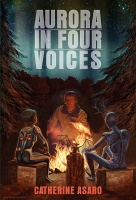

Aurora in Four Voices

Part of the Saga of the Skolian Empire

This limited edition anthology offers a selection of Catherine’s shorter fiction, stories set in the Saga of the Skolian Empire, also known as the Tales of the Ruby Dynasty. In 2011, when Catherine appeared as a Guest of Honor at the literary convention Windycon in Chicago, they released a limited edition collection of her work. Originally published by ISFic Press, the anthology gathers some of her shorter fiction into one volume. Titled Aurora in Four Voices after the Hugo and Nebula nominated novella of the same name, it has the following table of contents:

- Introduction, by Kate Dolan

- Aurora in Four Voices (Analog, 1998). Hugo nominated novella

- Ave de Paso, short story in Redshift: Extreme Visions of Speculative Fiction and Fantasy: the Best of 2001.

- The Spacetime Pool (Analog 2008), Nebula winning novella.

- Light and Shadow (Analog 1994), short story, first published tale in the Skolian saga.

- The City of Cries, novella in Down These Dark Spaceways (2005). Introduces Major Bhaajan mystery series.

- A Poetry of Angles and Dreams, essay written by Catherine about math concepts in her fiction.

- Afterword, by Aly Parsons

- Bibliography for Catherine’s work up through 2011

Start Reading

Aurora in Four Voices

Excerpt

Jump to Ordering Options ↓

Introduction to Aurora in Four Voices

![]()

I’m often asked how I think up story ideas. Although sometimes I can answer, for many stories I’m not sure. I have no idea how “Aurora in Four Voices” came about; it just evolved as I wrote. I already knew the character Soz; she appears a central figure in my Ruby Dynasty stories of the Skolian Empire. But the idea for a city of mathematical artists, geniuses who live in an endless night, striving to make beauty out of darkness—I have no clue what motivated that idea. This much I can say: it poured out of me at a time when I was a struggling writer with the earnest hopes of someday being published. The characters and the world seemed to write themselves, deepening each time I went over the story.

I sent “Aurora in Four Voices” to Stan Schmidt, the editor of Analog, more than twenty years ago. I’d previously accumulated several rejections from the magazine, but he had invited me to send more work. Although it the invite still came as a form letter, it offered a lifeline to a writer working so hard to find a professional home for her work. So I took a deep breath and sent him this novella. Although I can no longer remember exact dates, and my records are packed away in a box somewhere, I believe the letter Stan wrote to me about this story offered the first personalized editorial input I received from a major magazine after sending a story “blind” to the periodical. Stan found me in the proverbial slush pile.

“Aurora in Four Voices” didn’t become my first published story; those were “Dance in Blue,” a novelette that appeared in the David Hartwell anthology Christmas Forever, published first in 1993 and later in Steven Silver’s anthology Wondrous Beginnings from2003. My first Analog story was “Light and Shadow,” which appeared in 1994 and is reprinted elsewhere in this anthology.

“Aurora,” however, became my first cover story in Analog. It received nominations for both the Hugo and Nebula, to my jaw-dropping surprise. It “won” the first round of balloting for the 1999 Hugo in that sense that it had the most votes. However, it didn’t have quite enough to win according to the Australian balloting system (Worldcon was even in Australia that year). It went through all the rounds of the system, winning each, but never by enough, until the last round. On that one, Greg Egan’s “Oceanic” inched ahead and won by two votes. Although it was a disappointment, I’ve always loved Egan’s work; his “Wang’s Carpets” remains one of my favorite novellas. If I was going to lose to anyone, having it be an author I so greatly respected made it easier.

“Aurora in Four Voices” is among of my favorites of the stories I’ve written. I hope you enjoy reading the novella.

AURORA IN FOUR VOICES

Catherine Asaro

I

The Dreamers of Nightingale

He missed the sun.

The planet Ansatz boasted one city, Nightingale, a gem that graced eternal night. Just as a diamond sparkles because the light that ventures into its heart is captured, bouncing from face to face, so Jato Stormson was trapped in Nightingale. Unlike the light inside a faceted diamond, however, he could never escape.

After a few years, his memories of home faded. He could no longer picture the sun-parched farm on the planet Sandstorm where he had spent his boyhood. It was always dark in Nightingale.

The Dreamers—the artistic geniuses who had created Nightingale—were also mathematical prodigies. That was why they named their planet Ansatz. It referred to a method of solving differential equations. Make a guess, an ansatz, for the solution and see if it solved the equation. If it didn’t, make another guess. Another ansatz. Jato felt as if he were trapped on a guess of a world.

Tonight he went to the EigenDome, an establishment for dancing. He sat at a table and waited for the drink server, but no one came to his table. That was why he rarely visited the Dome. The artist who had designed the place considered it aesthetic to have humans serve the drinks, and the humans in Nightingale ignored him. But tonight he was lonelier than usual and even the icy Dreamers were better than no company at all.

Made from synthetic diamond, the Dome resembled a truncated soccer ball. Jato had looked up its history in the city library and found a treatise on how the Dome mimicked the spherical molecule buckyball. Its holographic lighting evoked the quantum eigenfunctions that described that molecular sphere. He didn’t understand the physics, but he appreciated the beauty it produced. Tonight Dreamers were everywhere, dancing, talking, humming. Centuries of playing with their genes and living in perpetual night had bleached their skin almost to translucence. Their hair floated around their bodies like silver smoke. Light from lamps outside the Dome refracted through the diamond walls, gracing the interior with rainbows that collected in pools of color. The Dreamers glistened like quantum ghosts.

Across the Dome, the doors abruptly opened. A spacer stood in the doorway, her body haloed by the rainbow light. This was no Dreamer. She looked solid. Sun-touched. She must have come in on one of the rare ships that visited Nightingale; rare, because the Dreamers allowed no immigration and most sun-dwellers found a city of unrelieved night too depressing for tourism. The only reason people came to Ansatz was to trade for a Dream.

Ah, yes. The Trade.

Dreamers made a simple offer; give one of them a pleasant dream and in return the Dreamer would give you a work of art. They allowed you ten days to try. After that, you had to leave Nightingale, trade or no trade. Considering the prices that Dreamer art claimed throughout the Imperialate, that trade seemed astoundingly one-sided, the offer of great treasure for no more than a nice dream.

Jato had let the lure of that promise fool him. He spent years saving for the ticket to Ansatz. But how do you give a dream? It was harder than it sounded, particularly given how sun-dwelling humans revolted the Dreamers. The same husky build and rugged looks that had won him such admiration back home repelled the Dreamers. Considering their disdain for ugliness, he feared they wouldn’t even let him stay the ten days.

They never let him go.

So now he sat by himself and watched the spacer walk to a table across in the Dome. The woman had no jacket; Nightingale’s weather machines kept the climate pleasant, free from the fierce winds the tore at the rest of Ansatz. She wore dark pants tucked into boots and a white sweater with gold rings on the upper arms. Her clothing seemed familiar, but Jato couldn’t place why. Her hair was a cloud of black curls with gold tips, and she had large eyes. Her skin had a dusky hue, full of rosy blooming health. None of the Dreamers spared her a second look, but Jato thought she was lovely.

She sat down—and a server showed up to take her order. Irked, Jato got up and headed for the laser bar, meaning to insist they serve him. Reaching the bar, however, was no simple feat. The Dome’s floor consisted of nested rings, each slowly rotating in one direction or the other. The book he had found in the library described some business about “mapping coefficients in quantum superpositions onto ring velocities.” All he knew was that it took a computer to coordinate the motion so patrons could step from one ring to another without falling. Dreamers carried it off with grace, but he had never mastered the skill.

Eventually he navigated his way to the dance floor, a languid disk turning in the Dome’s center. Dancers drifted away from him, slim and willowy, silver-eyed works of art. On the other side of the rotating disk, he ventured into the rings again and was soon being carried this way and that. Each time he neared a hovertable occupied by Dreamers, it floated away on cushions of air. He wished just once someone would look up, admit his presence, offer a greeting. Anything.Meanwhile, the server brought the spacer her drink, a Laser-Drop in a wide-mouthed bottle. Tiny lights in the glass suffused the drink with color: helium-neon red, zinc-selenium blue, sodium yellow. Drink in hand, she settled back to watch the dancers.

Jato quit pretending it was the bar he wanted and headed for the spacer. But whenever he neared her hovertable, people and tables that had been drifting away from him suddenly blocked his path. The spacer meanwhile finished her drink, slid a payment chip into the table slot, and headed for the door. He started after her—and the until then absent drink server suddenly appeared, blocking the way, his back to Jato, his tray of laser-hued drinks held high.

Jato scowled. He had always been long on patience and short on words, but even the most stoic man could only take so much. He put his hand against the server’s back and pushed, not hard, just enough to make the fellow move. The server stumbled and his tray jumped, rum splashing out of the jars in plump drops. Even then, no one looked at Jato, not even the server.

Gritting his teeth, Jato made his way to the door. Outside, lamps lit the entrance, but beyond their luminous circles, night reigned under a sky rich with stars. He strode away from the Dome, his fists clenched. He didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of seeing how well they provoked him.

The Dome was on the city outskirts, near the edge of the large plateau where the Dreamers had built Nightingale. The Giant’s Skeleton Mountains surrounded the plateau, falling away from it on three sides and rising in sheer cliffs on the fourth, here in the north. The peaks piled up higher and higher in the distance, until they become a jagged line against the star-dazzled sky. The Dreamers claimed they had built Nightingale as a challenge: can you create beauty in so forbidding a place? So they said. Jato had heard less savory reasons put forth for why they lived here in the dark, but the Dreamers denied them.

In the past, Jato’s attempts at convincing spacers to smuggle him off-planet had failed. He never gave up, though. In the distant shadows, the spacer was climbing the SquareCase, a set of stairs carved into a cliff. The first step was one centimeter high, the second four centimeters, the third nine, and so on, their heights increasing as the square of integers. The first twenty ran parallel to the cliff, but then they turned at a right angle and stepped into the mountains, rising taller and taller, until they became cliffs themselves, too high, too dark, and too distant to distinguish.

By the time he reached the SquareCase, the spacer was on the tenth step, a ledge about the height of her waist. She stopped and sat on it, half hidden in the dark while she watched him climb toward her. He approached slowly and stopped on the ninth step.

“Can I do something for you?” she asked.

“I wondered if you wanted a guide to the city.” It sounded unconvincing even to him, but it was the best introduction he could think of.

“Thank you,” she said. “But I’m fine.” The conversation screeched to a halt.

He tried again. “I don’t often get a chance to talk to anyone from off-planet.”

“I noticed my ship was the only one in port.”

`”Did you come to trade for a Dream?”

“No. Just minor repairs.” Her eyes were large in the dark. “I’ll be leaving as soon they’re done.”

Behind her, a distant globe appeared, sparkling with lights in a fractal pattern. It floated forward, over a meter in diameter, its surface patterned by delicate curls of the Mandelbrot set, swirls fringed by swirls fringed by swirls in an unending pattern of ever more minute lace.

Following his gaze, the woman glanced back. “What is that?”

“A robot drone. It monitors this staircase.”

She turned back to him. “Why does that make you angry?”

“Angry?” How had she known? “I’m not angry.”

“What does it do?” she asked.

“I’ll show you.” Jato hauled his muscular bulk onto the tenth step. Although he towered over the spacer, she seemed unperturbed, simply scooting over to let him pass. That self-confidence impressed him as much as her beauty. When he stepped toward the eleventh step, the globe whirred into his face. When he tried to push it away, the robot rammed his shoulder so hard he fell to one knee.

“Hey!” The woman jumped up and grabbed for him, as if she actually thought she could stop someone his size from falling. “Why the blazes did it do that?”

He stood up, brushing rock dust off his trousers. “As a warning.”

That’s when she did it. She smiled. “Whatever for?”

Jato hardly heard her. All he saw was her smile. It dazzled.

After a moment, her smile faded. “Are you all right?” she asked.

He refocused his thoughts. “What?”

“You’re just staring at me.”

“Sorry.” He motioned at the globe. “It was warning me to stay within the city border, which crosses the cliff here.” Having the drones watch him up here was almost funny. As if he could actually escape Nightingale by climbing a staircase that grew geometrically.

“Why can’t you leave the city?” she asked.

He couldn’t tell her, not yet. Eight years ago, the Dreamers had showed up at his room in the Whisper Inn and locked his wrists behind his back with cuffs made from sterling silver Mobius strips. He hadn’t had any idea what was happening until they put him on trial. They convicted him of a murder that had never happened and sentenced him to life in prison.

Supposedly, years of treatment had “cured” him, and he no longer posed a danger to society. So the Dreamers had let him out of his cell, which had never been a cell anyway but an apartment under the city. For a giddy span of hours he had thought they meant to send him home; if he was no longer dangerous, why keep him under sentence?

He soon found out otherwise.

For the Dreamers who believed in his guilt, which was most of them, it would take a lifetime for him to atone. One of their most renowned artists, a man called Crankenshaft Granite, had argued that it would be almost as much a punishment for a man like Jato to spend his life confined to Nightingale as it was to confine him to a single apartment. But by making the city his jail, they showed their compassion for a criminal who had turned away from his violent nature. Jato saw why that logic appealed to the Dreamers, who for some reason had a driving need to see themselves as kind, yet who scorned all sun-dwellers and saw them deserving of neither freedom nor friendship.

It was all lies. He knew the truth. Crankenshaft’s motives had nothing to do with compassion. The only reason Jato had even a modicum more freedom now was because it made Crankenshaft’s life easier.

Jato didn’t want to see that wary look on this woman’s face, the one spacers wore when they learned his story. Not yet. He wanted these few minutes without the weight of his murder conviction pressing on them. So instead of telling her, he pointed at his feet and made a joke. “This is where I live. These are my coordinates.”

She blinked. “Your what?”

So much for his scintillating wit. “Coordinates,” he repeated. “This staircase is the plot of a non-linear step function.”

She laughed like the sweet ringing of a bell. “Why would anyone go to all this work just to make a big plot?”

“It’s art.” He wished she would laugh again. It was a glorious sound.

“This is some art,” she said. “But you haven’t told me why your people won’t letyou leave.”

His people? She thought he was a Dreamer? That would have been funny if it wasn’t so absurd. It wasn’t only that he bore no resemblance to the ethereal Dreamers. They were also gifted at art and mathematics, neither of which he had talent for. Yet this beautiful woman thought he was both.

Jato grinned at her. “They like me. They don’t want me to go.”

She stared at him, her mouth opening.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

She closed her mouth and a blush touched her cheeks. “What?”

“You’re just staring at me.”

“I—your smile—” Her blush deepened. “My apologies. I’m rather tired.” She gave him a formal nod. “My pleasure at your company.” With that, she headed back down the stairs.

He almost went after her, stunned by her abrupt leave-taking. But he managed to keep from making a fool of himself. Instead, he stood in the shadows and watched her descend the SquareCase.

![]()

Jato turned into the underground corridor that dead-ended at his apartment—and found a Mandelbrot globe waiting at the door. Given that he lived nowhere near Nightingale’s perimeter, only one reason existed for its presence here. Crankenshaft had sent it. With Jato no longer confined to his apartment, Crankenshaft could have his robotic minions bring Jato to him rather than the Dreamer having to come down here.

Jato spun around and ran, his boots clanging on the metal floor. If he could find a side passage too narrow for the globe to follow, he might escape. It was a stupid game Crankenshaft played; if Jato evaded capture, Crankenshaft let him have the day off.

A whirring came from behind him. The drone hit his side and he stumbled into the wall, bringing up his arms to protect his face. An aperture opened on the globe and an air syringe slid out, accompanied by an ugly hiss as it shot him.

His view of the hall wavered, darkened, faded …

![]()

Jato slowly opened his eyes. A face floated above him, an aged Dreamer with eyes like ice. Gusts of wind fluttered her silver hair around her cheeks. He knew that gaunt face. It belonged to Silicate Glacier. Crankenshaft’s wife.

Crankenshaft was standing behind her. Tall for a Dreamer, he had a well-kept physique that belied his one hundred and six years of age. Black hair covered his head in bristles. He had two-tone eyes, grey bordered by red, like old ice in ruby rings.

Jato spoke hoarsely. “How long?”

“You have slept several hours,” Crankenshaft said.

“I meant, how long do you need me for?” Jato rasped. He felt as if a maglev had hit him.

“I don’t know,” Crankenshaft said coolly. “We will see.”

As Jato sat up, Silicate stepped back, avoiding contact with him. He swung his legs over the stone ledge where he had been lying. Crankenshaft had chosen the big studio today. This shelf jutted out of the west wall, an otherwise blank plane of grey stone. On the left, the south wall was a window that looked over Nightingale, which lay far below. The east and north “walls” were holo-screens, sheets of thermoplastic that hung from the ceiling. Holos rippled in front of them, swaths of color that trembled as breezes shook the screens.

That machine-created wind always disoriented Jato. Moving air didn’t belong inside a house. For that matter, neither did Mandelbrot globes. But two floated here, one hovering behind Crankenshaft and another prowling the studio.

The major feature in the room was a round pool. A glossy white cone about two meters tall rose out of the water. A second cone stood next to it, its top cut flat in a circular cross-section. The three other cones in the pool were cut at angles, giving them elliptical, parabolic, and hyperbolic cross-sections.

“Circle today,” Crankenshaft said. Then he headed across the drafty studio to a console standing where the two holo-walls met.

Jato looked at Silicate and she looked back, as cool and as smooth as stone. Then she too walked away, leaving the studio via a slit in a thermoplastic wall.

A gust rumpled Jato’s hair and he shivered, wrapping his arms around his body. “Do you have a jacket?” he asked.

Crankenshaft didn’t answer, he just stooped over his console and went to work. So Jato waited, trying to clear out the haze left in his mind by the sedative.

A globe nudged his shoulder. When he stayed put, it pushed harder. “Flame off,” he muttered.

A syringe extended out of the globe.

Still intent on his console, Crankenshaft said, “The syringe shoots a heat stimulant. A strong specimen such as yourself might tolerate it for ten minutes before going into shock.”

Jato scowled. Where did Crankenshaft come up with this sick stuff? He looked at the globe, at Crankenshaft, at the globe. He used care in choosing his battles, and this one wasn’t worth it.

He took off his boots and went to the pool. The knee-deep water was cool today, but at least no ice crusted the surface. He waded to the truncated cone and climbed onto it, then sat cross-legged, hugging his arms to his chest for warmth.

“Move ten centimeters to the north,” Crankenshaft said.

Jato moved over. “Can you warm it up in here?”

Crankenshaft sat at his console, concentrating on whatever he was doing. So Jato moved to the south side of the cone.

The Dreamer looked up. “I said move to the other side.”

“Turn on the heat,” Jato said.

“Move.”

“After you turn on the heat.”

Stalemate.

Crankenshaft touched a panel on the console. A globe whirred behind Jato and a syringe hissed. Heat flared in his biceps, spreading fast, up his shoulder and down his arm.

“Hot enough?” Crankenshaft asked.

It was excruciating, but Jato had no intention of letting his tormentor know. He just shrugged. “What will you do? Put your model into shock because he objects to freezing?”

A muscle under Crankenshaft eye twitched. He went back to work, ignoring Jato. However, the room warmed and the burning in Jato’s muscles cooled. Either Crankenshaft had lied about the poison or else the drone had delivered an antidote with it, probably in a bio-sheath that dissolved after a few minutes in the blood.

Over the next few hours the wind dried Jato’s clothes. Silicate came in once to bring Crankenshaft a meal on a stone platter. Jato wondered about her, always attentive, always silent. Did she create her own art? Most Dreamers did, even those who worked other jobs. Silicate’s only occupation seemed to be waiting on Crankenshaft. But then, Jato doubted her husband would tolerate artistic competition in his own household.

Finally Crankenshaft stood up, rolling his shoulders to ease the muscles. “You can go,” he told Jato. With that, he strode out of the studio.

Jato gritted his teeth. Just like that. You can go. Get out of my house. He slid off the cone and limped through the water in the pool, sore from sitting so long. He coaxed on his boots on under his wet trousers and then went to a door in the corner of the studio where the window-wall met one of the thermoplastic walls.

Icy wind greeted him outside. He came out at the top of a staircase that spiraled down this cliff that Crankenshaft owned. The city glimmered far below and beyond it a ragged landscape stretched into the darkness. Millennia ago a marauding asteroid had struck this planet, distorting it into a blunt teardrop that lay on its side, its axis pointed at Quatrefoil, the star it orbited. Although Ansatz was almost tidally locked with Quatrefoil, it wobbled enough so that most of its surface received at least a little sunlight. Night reigned supreme only here in this region around the pole.

Crankenshaft’s estate was high enough to touch the transition zone between the human-made pocket of calm around Nightingale and the violent winds that swept Ansatz. Yet despite the long drop to the plateau, the staircase here had no protection, not even a rail. Another of Crankenshaft’s “quirks.” After all, he never used these stairs.

Jato exhaled, calming his pulse. When he came willingly, Crankenshaft always had a flycar waiting to take him home. Today he would have to go back inside and ask for a ride, a prospect he found about as appealing as eating rocks.

So instead he went down the stairs, stepping with care, always aware of the chasm of air that surrounded him. Around and around the spiral he went, never looking down, lest it throw off his balance. He wondered how he appeared to someone looking up here from down in the city. he was a mote descending a stone DNA helix on the face of a massive cliff.

The helix image caught his mind. A sculpture. He imagined how he would design the piece. He could go to the library and find a text on DNA. It would have to be a holobook, though, rather than anything on the computer.

Before Jato had come to Ansatz, his computer illiteracy hadn’t mattered. As the son of an impoverished water-tube farmer on Sandstorm, he hadn’t been able to afford any mesh access, let alone a smart console. Although everyone here in Nightingale had access to the city mesh, it did him little good. He didn’t know how to use it. However, he had managed to figure out how he could tell a console in the library to make him print books.

Jato wondered if he should even bother with helix sculpture. Reading could only give him information, not talent. One thing he had to say for Crankenshaft: the man was brilliant. Jato could never imagine Crankenshaft giving away his stratospherically priced work for a Dream. Besides, what Dream would he find pleasant? Pulling the wings off bugs, maybe.

A few Dreamers in Nightingale’s city government knew Crankenshaft had set Jato up. They had framed him for a crime so brutal it would have meant execution or personality reconfiguration anywhere else. That left him no choice; either he stayed here or he became a fugitive. Imperialate law gave no quarter: an escaped convict fleeing into a new jurisdiction could be resentenced there for his crime. That often-denounced law was intended to ease the morass of extradition problems that arose as more and more planets came under Imperial rule. But it let Crankenshaft blackmail him; if Jato ever left Nightingale, he was subject to death or a brain wipe.

Crankenshaft’s work was known across a thousand star systems. He was a genius among geniuses, and on Ansatz that translated into power. Whatever he wanted for his art, he was given.

Including Jato.

end of excerpt

Aurora in Four Voices

is available in the following formats:

Digital:

- See The Spacetime Pool anthology for an eBook with some of these stories.